|

Longstanding Problems and New Realities This chapter examines the current state of higher education in developing countries, and considers the new realities they face and how they are reshaping ongoing challenges. In the past decades, developing countries have witnessed a rapid expansion of higher education, the simultaneous differentiation of higher education institutions into new forms, and the increasing importance of knowledge for social and economic development[4]. We focus on issues affecting most developing countries – exceptions exist, but should not affect the main thrust of our argument. In subsequent chapters we explore the strategies and initiatives that are needed to meet these challenges. Higher education institutions clearly need well designed academic programs and a clear mission. Most important to their success, however, are high-quality faculty, committed and well prepared students, and sufficient resources. Despite notable exceptions, most higher education institutions in developing countries suffer severe deficiencies in each of these areas. As a result, few perform to a consistently high standard. Faculty Quality A well qualified and highly motivated faculty is critical to the quality of higher education institutions. Unfortunately, even at flagship universities in developing countries, many faculty members have little, if any, graduate-level training. This limits the level of knowledge imparted to students and restricts their ability to access existing knowledge and generate new ideas. Teaching methods are often outmoded. Rote learning is common, with instructors doing little more in the classroom than copying their notes onto a blackboard. The student, who is frequently unable to afford a textbook, must then transcribe the notes into a notebook, and those students who regurgitate a credible portion of their notes from memory achieve exam success. These passive approaches to teaching have little value in a world where creativity and flexibility are at a premium. A more enlightened view of learning is urgently needed, emphasizing active intellectual engagement, participation, and discovery, rather than the passive absorption of facts. Improving the quality of faculty is made more difficult by the ill-conceived incentive structures found in many developing countries. Faculty pay is generally very low in relation to that offered by alternative professional occupations. Pay increases are governed by bureaucratic personnel systems that reward long service rather than success in teaching or research. Market forces, which attempt to reward good performance, are seldom used to determine pay in the higher education sector. While pay disparities make it difficult to attract talented individuals, recruitment procedures are often designed in ways that hinder intellectual growth. Some developing countries have been slow to develop traditions of academic freedom and independent scholarship. Bureaucracy and corruption are common, affecting the selection and treatment of both students and faculty (see Chapter 4). Favoritism and patronage contribute to academic in breeding that denies universities the benefit of intellectual cross-fertilization. These problems arise most commonly in politicized academic settings, where power rather than merit weighs most heavily when making important decisions. Politicization can have a wider impact on the atmosphere of a system. While political activity on campuses throughout the world has helped address injustices and promote democracy, in many instances it has also inappropriately disrupted campus life. Research, teaching, and learning are extremely difficult when a few faculty members, students, and student groups take up positions as combative agents of rival political factions. Higher education institutions rely on the commitment of their faculty. Their consistent presence and availability to students and colleagues has an enormous influence in creating an atmosphere that encourages learning. Yet few institutions in developing countries enforce, or even have, strictures against moonlighting and excessive absenteeism. Many faculty work part-time at several institutions, devote little attention to research or to improving their teaching, and play little or no role in the life of the institutions employing them. Faculty members are often more interested in teaching another course – often at an unaccredited school – rather than increasing their presence and commitment to the main institution to with which they are affiliated. With wages so low, it is hard to condemn such behavior. Problems faced by students In many institutions, students face difficult conditions for study. Severely overcrowded classes, inadequate library and laboratory facilities, distracting living conditions, and few, if any, student services are the norm. The financial strains currently faced by most universities are making conditions even worse. Many students start their studies academically unprepared for higher education. Poor basic and secondary education, combined with a lack of selection in the academic system, lie at the root of this problem. Yet rarely does an institution respond by creating remedial programs for inadequately prepared students. Cultural traditions and infrastructure limitations also lead to students studying subjects, such as humanities and the arts, that offer limited job opportunities and lead to “educated unemployment”. At the same time, there is often unmet demand for qualified science graduates (see Chapter 5), while in many societies women study subjects that conform to their traditional roles, rather than courses that will maximize their opportunities in the labor market. Better information on the labor market is needed, combined with policies that promote economic growth and labor absorption. Also, many educated people tend to be from wealthier backgrounds and are able to resist taking jobs in locations they consider to be undesirable. Promoting an entrepreneurial culture will encourage the creation of more productive jobs. Students also face the widespread requirement to choose their area of specialization early in their course, in some cases ahead of matriculation. Once a choice is made, change is frequently difficult or impossible. Such inflexibility closes off options, with students unable to sample courses in different academic areas. Early specialization can prevent costly indecisiveness, but systems that are unforgiving of early “mistakes” do not develop and unleash the true potential of many students. Insufficient Resources and Autonomy Many of the problems involving higher education are rooted in a lack of resources. For example, developing countries spend far less than developed countries on each student. But finding new funds is not easy. Although absolute spending is low, developing countries are already spending a higher proportion of their smaller incomes than the developed world on higher education, with public spending growing more quickly than income or total government spending. Higher education is clearly placing greater demands on public budgets[5], with the private sector and international donors taking up only some of the slack. Redirecting money from primary or secondary education is rarely an option, with spending per student on higher education already considerably higher than is common at other levels of the education system. Most public universities are highly dependent on central governments

for their financial resources. Tuition fees are often negligible

or non-existent, and attempts to increase their level encounter

major resistance. Even when tuition fees are collected, the funds

often bypass the university and go directly into the coffers of

ministries of finance or central revenue departments. Budgets must

typically be approved by government officials, who may have little

understanding of higher education in general, of the goals and capabilities

of a particular university, or of the local context in which it

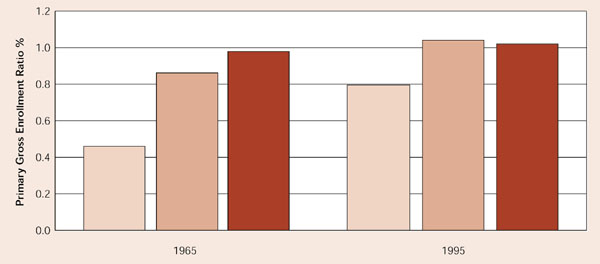

operates. In addition, capital and operating budgets are poorly coordinated. Major new facilities are built, but then are left with no funds for operation and maintenance. The developing world is littered with deteriorating buildings, inadequate libraries, computer laboratories that are rarely open, and scientific equipment that cannot be used for want of supplies and parts. It is often impossible to carry over unspent funds for use in later years, and difficult to win a budget that is higher than the previous year’s actual expenditure. This creates a”use-it-or-lose-it environment”, resulting in overspending and misspent resources. Research universities face an array of especially serious problems. Their role derives from a unique capacity to combine the generation of new knowledge with the transmission of existing knowledge. Recent pressures to expand higher education, discussed at length below, have in many cases diverted such universities from pursuing research, and their financial situation is further diminishing their research capabilities. Public universities in Africa and Asia often devote up to 80 per cent of their budgets to personnel and student maintenance costs, leaving hardly any resources for infrastructure maintenance, libraries, equipment, or supplies – all key ingredients in maintaining a research establishment. The disappearance of a research agenda from these universities has serious consequences. The inability to pursue research isolates the nation’s élite scholars and scientists, leaving them unable to keep up with developments in their own fields. As research universities lose their ability to act as a reference point for the rest of the education system, countries quickly find it harder to make key decisions about the international issues affecting them. In addition to being severely underfunded, sometimes despite their best efforts, many higher education institutions in developing countries lack the authority to make key academic, financial, and personnel decisions. They can also be slow to devolve responsibility for decision-making to constituent departments. Poor governance, in other words, dilutes their ability to spend what money they have. Expansion of Higher Education Systems Problems of quality and lack of resources are compounded by the new realities faced by higher education, the first of which is expansion, as higher education institutions battle to cope with ever-increasing student numbers. Responding to this demand without further diluting quality is an especially daunting challenge. Figure 2 - Average Primary Gross Enrollment Ratios by National Income, 1965 and 1995

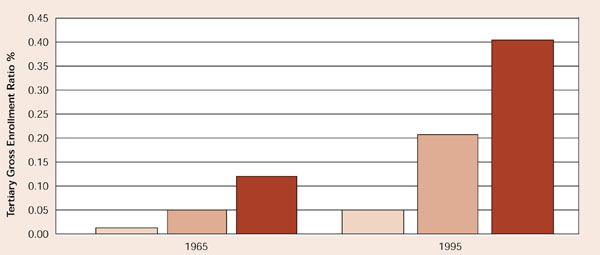

Precursors In the past 50 years educational development has focused on expanding access to primary education. Starting from a low base, the results have been extraordinary. In 1965, less than half the adult population of developing countries was literate – less than one-third in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. By 1995, however, 70 per cent of adults living in developing countries were literate, with literacy levels above 50 per cent even in sub-Saharan Africa. Primary school enrollments have skyrocketed, with variations in performance between rich and poor countries shrinking rapidly. As increasing numbers of students complete primary school, demand for access to secondary education rises. In recent decades, secondary enrollment ratios have increased significantly, and further expansion is almost certain. For example, between 1965 and 1995 the secondary gross enrollment ratio[6] increased from 16 to 47 per cent in Brazil, from five to 32 per cent in Nigeria, and from 12 to 30 per cent in Pakistan. This has a double impact on higher education. More secondary students would mean more people entering higher education, even if the proportion progressing remained constant. However, the proportion who do want to graduate to higher education is increasing substantially, as globalization makes skilled workers more valuable and the international market for ideas, top faculty, and promising students continues to develop. The substantial widening of access to primary and secondary education has combined with two other factors to impel the expansion of the higher education system: (i) a rapid increase in the number of people at the traditional ages for attending higher education institutions[7], and (ii) a higher proportion of secondary school graduates progressing to higher education. Demographic change, income growth, urbanization, and the growing economic importance of knowledge and skills, have combined to ensure that, in most developing countries, higher education is no longer a small cultural enterprise for the élite. Rather, it has become vital to nearly every nation’s plans for development. As a result, higher education is indisputably the new frontier of educational development in a growing number of countries (Figure 3). The number of adults in developing countries with at least some higher education increased by a factor of roughly 2.5 between 1975 and 1990. In 1995 more than 47 million students were enrolled in higher education in the developing world, up from nearly 28 million in 1980. For most developing countries, higher education enrollments are growing faster than their populations, a trend that will continue for at least another decade. This continued expansion of higher education is clearly necessary to meet increased demand. However, it has brought with it some new problems. For example China, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Russia now have systems of higher education serving 2 million or more students. A further seven developing countries – Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, Iran, Mexico, Thailand, and Ukraine – enroll between 1 and 2 million students. To accommodate so many students, some institutions have had to stretch their organizational boundaries severely, giving birth to 'mega-universities' such as the National University of Mexico and the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina, each of which has an enrollment of more than 200 000 students. Expansion, both public and private, has been unbridled, unplanned, and often chaotic. The results – deterioration in average quality, continuing interregional, intercountry, and intracountry inequities, and increased for-profit provision of higher education – could all have serious consequences. Imbalances Although higher education enrollment rose sharply between 1980

and 1995 in both industrial and developing countries, the enrollment

rate in industrial countries has remained roughly five to six times

that in developing countries. Within countries there are major imbalances between urban and rural areas, rich and poor households, men and women, and among ethnic groups. We know of no country in which high-income groups are not heavily over-represented in tertiary enrollments. For example in Latin America, even though the technical and professional strata account for no more than 15 per cent of the general population, their children account for nearly half the total enrollment in higher education, and still more in some of the best public universities such as the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas in Brazil, the Simón Bolivar University in Venezuela, and the National University of Bogotá in Colombia. From 1965 to 1995 the female share of enrollment in higher education in the developing world increased from 32 to 45 per cent. Female enrollment is driving nearly half of the increased demand for higher education, and will presumably promote greater gender equality. But at present, outside the industrial countries only Latin America and the countries in transition have achieved overall gender balance. Figure 3 - Average Tertiary Gross Enrollment Ratios by National Income, 1965 and 1995

Differentiation of Higher Education Institutions Alongside the worldwide expansion of higher education systems, the nature of the institutions within these systems has also been shifting, through a process of differentiation. Differentiation can occur vertically as the types of institutions proliferate, with the traditional research university being joined by polytechnics, professional schools, institutions that grant degrees but do not conduct research, and community colleges. Differentiation can also occur horizontally by the creation of new institutions operated by private providers, such as for-profit entities, philanthropic and other non-profit organizations, and religious groups. The spread of distance learning operations is an increasingly important example of differentiation and has both vertical and horizontal features. Private education in developing countries has been growing since the 1960s. Not all this growth has been in for-profit institutions; private philanthropic institutions have also been expanding. These are not-for-profit institutions relying on a combination of gifts and fees. Philanthropic institutions have played a particularly significant role in providing high-quality education, although narrowly defined and strongly rooted objectives can limit the extent to which many are able to advance the wider public interest. They generally sit somewhere between public and for-profit institutions, sharing some of the strengths, weaknesses, and objectives of each. In many contexts the distinction between for-profit and not-for-profit private institutions is often of greater practical significance than the more traditional division between public and private institutions, since not-for-profit private institutions frequently resemble public institutions in terms of their mission and their structure. Horizontal differentiation The growth of private higher education institutions, especially for-profit institutions, is the most striking manifestation of differentiation. Although the exact scale of private expansion is difficult to determine, the number of private institutions increased dramatically in many parts of Asia and Africa from the 1980s onwards – a process that started much earlier in Latin America, where institutions with religious affiliations are strong. China now has more than 800 private higher education institutions, although the Ministry of Education officially recognizes only a handful of them. Nearly 60 per cent of Brazil's tertiary-level students are currently enrolled in private institutions, which comprise nearly 80 per cent of the country’s higher education system. At independence in 1945 Indonesia had only 1000 tertiary-level students. It now has 57 public universities and more than 1200 private universities, with more than 60 per cent of the student body enrolled in private institutions. In South Africa, roughly half of the country's students are enrolled in private institutions (see Figure 4). This trend seems certain to continue. Deregulation in many countries is loosening the state's grip on the founding and operation of private institutions. Where demand has built up, growth is likely to be especially strong. A growing private sector does not necessarily lead to increased diversity, as new universities may simply imitate the curricular offerings of the public universities (as has tended to happen in Latin America). In general, though, new private institutions are likely to be somewhat innovative, if only because they do not have an institutional history to overcome. The ability to respond to the market and greater legal freedom may also be important. Private universities in South Asia, for example, have introduced innovations in the form of the semester system, standardized examinations, and credit systems. Figure 4 - Percentage Share of Enrollment in Private Higher Education Click image to enlage [size 80KB]

The creation of new universities by religious organizations is a particularly important phenomenon. For example, the United Methodist Church established the African University in Zimbabwe, with department heads selected from among nationals of different African countries. Well-established religious universities – Protestant, Catholic, and Muslim – operate in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. A similar phenomenon involving Catholic universities occurs in Latin America. Distance learning, in which students take classes primarily via radio, television, or the Internet, has expanded enormously during the past decade. (Both Nelson Mandela and Robert Mugabe earned their degrees in this way, at the world’s oldest distance-learning university, the University of South Africa.) The five largest programs in the world are all based in developing countries, and all of these have been established since 1978 (see Table 1). They claimed an aggregate enrollment of roughly 2 million students in 1997, and account for about 10 per cent of enrollment growth in developing countries during the past two decades. Educators have long been using radio and television to reach students in remote areas, but new satellite- and Internet-based technologies promise to extend distance-learning systems to a broader group of students, ranging from those in sparsely populated, remote areas to those living in dense urban agglomerations. In the USA, for example, the University of Phoenix is vigorously promoting its online courses, while in the UK, the publicly funded Open University has over 100 courses that use information technology links as a central part of the teaching – with 4000 students per day connecting via the Internet. Distance learning has great potential in the developing world, offering a powerful channel for bringing education to groups that have previously been excluded. In the future it is almost certain to take place increasingly across borders. Already over 12 per cent of the UK’s Open University students are resident outside the country. It is also easy to conceive of high-quality developing country institutions offering educational programs and degrees in other parts of the developing world. While a desirable development, this would create a variety of problems relating to quality control and other forms of supervision. Table 1 - Ten largest distance-learning institution

Vertical differentiation While horizontal differentiation is driven by increased demand for higher education, vertical differentiation is a reaction to demand for a greater diversity of graduates. In general, economic development is associated with a more refined division of labor, and higher education institutions have an essential role to play in imparting necessary skills. The increasing importance of knowledge makes this range of skills in wider demand than ever. Today’s developing economy needs not only civil servants, but also a whole host of other professionals such as industrial engineers, pharmacists, and computer scientists. Higher education institutions are adapting and new ones are emerging to provide training and credentials in new areas. As societies accept modern medicine, for example, they establish not only medical schools, but also schools of pharmacy. The labor market also creates a demand for graduates who have undergone training of different types and intensities. Both public and private institutions have responded by creating academic programs that accommodate students with a wider range of capabilities. Some new programs allow students to earn lower-ranking degrees relatively quickly. In Bangladesh, some universities have two streams of undergraduate students: one that is admitted for a standard 3-year bachelor's program, and another that is admitted to a less demanding 2-year program. Both groups take the same classes, with less-advanced students having to complete fewer courses to graduate. As enrollments increase, new specialties can develop, attracting the critical mass of students and faculty that allow institutions to set up new departments, institutes, and programs. Differentiation is spurred on by the relaxation of state regulations, but this poses serious quality problems. The argument that market forces will ensure suitable quality is simplistic. Private institutions often receive public subsidies through tax deductions on financial contributions or donations of physical facilities from public sources, or by accepting students whose tuition is financed by the government. To the extent that competition is driven by cost alone, it is likely to abet the provision of low-quality education. So-called garage universities sometimes disappear as quickly as they appeared, leaving students with severe difficulties in establishing the quality of their credentials. The expansion and differentiation of higher education is occurring at the same time as the pace of knowledge creation is dramatically accelerating. The categories into which new knowledge falls are becoming increasingly specialized, and a revolution has occurred in people’s ability to access knowledge quickly and from increasingly distant locations. These changes are fundamentally altering what economies produce, as well as where and how they produce it. Organizations are changing, as are the skills needed to run them and the way they utilize human capital. Industrial countries have been by far the greatest contributors to, and beneficiaries of, this knowledge revolution. To the extent that this trend continues, the income gap between industrial and developing countries will widen further. Higher education institutions, as the prime creators and conveyors of knowledge, must be at the forefront of efforts to narrow the development gap between North and South. Characteristics of the revolution The knowledge revolution can be described in a few key dimensions.

The spectacular advances in recent decades in computerization, communications, and information technology have greatly enhanced the ability of researchers and entrepreneurs to create new knowledge, products, and services. Developments in electronics and computerization in the 1950s and 1960s laid the groundwork for incorporating microprocessors into a totally unanticipated array of devices, thereby transforming old machines into newly 'smart' ones, while creating new machines at a breathtaking pace. New services have proliferated, transforming labor-intensive tasks such as managing payroll and travel reservation systems into technology-based activities. Factory production is increasingly based on robotics and sophisticated computer controls. Even automobile mechanics use computer-based analytical tools. In recent years advances in communications and information technology have taken center stage. Fax machines have turned many isolated offices into active nerve centers, only to be superseded by electronic mail. Massive databases have consolidated huge quantities of information in one place, thereby allowing academics, entrepreneurs, and the general public to tap into them conveniently and rapidly. Most recently, the Internet has allowed people to access information about an unprecedented number of topics virtually instantly and, in most cases, cheaply. One of the factors underlying these changes is a dramatic reduction in the cost and ease of transmitting data. It will soon be possible to transmit 100 times as much data, for approximately one-hundredth the cost, as in 1983. Beyond all these advances lie revolutions in other fields. New techniques in genetics and molecular biology have made possible new products, therapies, and cures, all of which promise radically to transform the quality of life. Chemists, physicists and engineers have created new materials and processes, propelling plastics and ceramics into the heart of industrial operations and adopting fiber optics as the lifeblood of international communication. These changes are also creating formidable new geopolitical, ethical, legal, and human rights issues related to, for example, the development of new weapons, the possibilities inherent in cloning, and the threat to privacy posed by centralized databases and their phenomenal reach.

Implications for Developing Countries The increasing importance of knowledge, in conjunction with the fact that most developing countries are falling further behind in their ability to create, absorb, and use it, has some major implications for developing countries.

Implications for Higher Education Knowledge has become a springboard for economic growth and development, making the promotion of a culture that supports its creation and dissemination a vital task. Policy-makers must keep a number of considerations in mind.

In most developing countries higher education exhibits severe deficiencies, with the expansion of the system an aggravating factor. Demand for increased access is likely to continue, with public and private sectors seeking to meet it with an array of new higher education institutions. Rapid and chaotic expansion is usually the result, with the public sector generally underfunded and the private (for-profit) sector having problems establishing quality programs that address anything other than short-term, market-driven needs. A lack of information about institutional quality makes it difficult for students to make choices about their education, making it hard to enlist consumer demand in the battle to raise standards. Developing countries are left with a formidable task – expanding their higher education system and improving quality, all within continuing budgetary constraints. [4]

We realize that the differentiation of higher education institutions

is not a new phenomenon, as different types of colleges and universities

have existed for centuries. What is new, however, is the strength

of the forces driving differentiation, the pace at which it is occurring,

and the variety of institutions being created. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||